Can Fibroids Cause Problems with Bleeding and Fertility?

Fibroids bulging into the uterine cavity or within the cavity (submucous fibroids) can sometimes cause heavy menstrual bleeding or infertility. Submucous fibroids can often be removed with a hysteroscope, a telescope placed through the cervix and into the uterus. A study that combined results from many small studies found that submucous fibroids that change the shape of the uterine cavity decreased pregnancy rates by 70%. And, when these fibroids were removed there was an increase in the pregnancy rates by 70%.

The reason submucous fibroids can lead to infertility is not clear, but current theories are that the fibroids change blood supply to a developing embryo, or block passage of the embryo through the fallopian tube, or cause inflammation in the uterine lining, or produce proteins that interfere with the embryo’s journey through the tube, its attachment to the uterine lining or its development.

The way submucous fibroids cause heavy bleeding is also not clear, but most studies show removing these fibroids cures heavy bleeding. One study of women with very heavy bleeding found that, after removal of fibroids by hysteroscopy, additional surgery was needed by only about 10% of the women within 2 years, by 11% after 5 years and by 27% after 8 years.

What Is a Hysteroscopic Myomectomy?

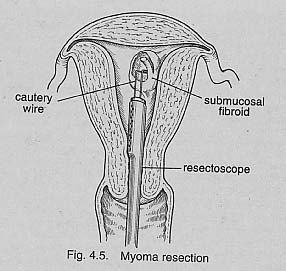

Hysteroscopic myomectomy is a technique that can be performed only if fibroids are within or bulging into the uterine cavity (submucosal). This procedure is performed as outpatient surgery without any incisions and virtually no postoperative discomfort. Anesthesia is needed because the surgery may take one to two hours and would otherwise be uncomfortable. A small telescope, the hysteroscope, is passed through the cervix and the inside of the uterine cavity can be seen. A small camera is attached to the telescope and the view is projected on a video monitor. This magnifies the picture and also allows the physician to perform the surgery while sitting in a comfortable position.

Electricity passes through the thin wire attachment at the end of the hysteroscope, allowing the instrument to cut through the fibroid like a hot knife cutting through butter. As the fibroid is shaved out, the heat from the instrument sears blood vessels and the blood loss is usually minimal. Women go home the same day, and recovery is remarkably fast, with most patients able to go back to normal activity, work and exercise in one or two days.

When fibroids are the cause of infertility, pregnancy rates following hysreroscopic myomectomy have been about 50%. And when performed for heavy bleeding, nearly 90% of women have a return of normal menstrual flow.

Only a few years ago, treatment for fibroids in the cavity of the uterus involved major surgery-an abdominal incision and either cutting open the entire uterus to remove the fibroid or performing a hysterectomy. Hysteroscopic myomectomy has been a major advance in the treatment of women who have submucous fibroids.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nE7EcCF6NIM

Hysteroscopic Myomectomy (Graphic Footage)

What is Endometrial Ablation?

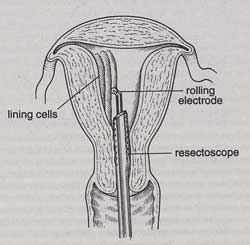

Endometrial ablation is an outpatient procedure used to stop or decrease bleeding from the uterus. The traditional method of performing endometrial ablation uses electrical energy passed into the uterine cavity at the end of a telescope in order to cauterize and destroy the lining of the uterus. This technique is very effective, but does require special training and skill on the part of the doctor. As a result, many doctors never learned how to perform endometrial ablation and do not offer the procedure to their patients as an alternative to hysterectomy.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sEOJ_W5LG5Y

New! Video of Dr. Parker performing an Endometrial Ablation. To manage heavy bleeding, the small (1/4 inch) rolling metal bar can be used to cauterize and eliminate the uterine lining cells.

(Graphic Footage)

Other methods of ablation have recently been developed. One procedure, called Hydrothermal Ablation (HTA), uses hot water circulated inside the uterus to destroy the lining cells. This device is specially engineered to keep the water at a low pressure so that it cannot escape through the tubes. If the device senses a leak, it automatically shuts off. Because the water circulates freely throughout the entire uterine cavity, the shape of the cavity does not affect the results. As a result, the device is very effective for women with fibroids or enlarged uterine cavities. Hydrothermal Ablation takes about 10 minutes and results are excellent.

Both types of procedures are offered in our practice depending on which is appropriate for the individual situation. With either procedure all the lining cells get destroyed in about 50% percent of patients and these women never have another menstrual period again. An additional 40% percent of women only experience a light flow for a few days each month because a few lining cells have been left behind. About 10% of women have no improvement noted. Thus, 90% of the women who have this procedure, all of whom have had severe and debilitating monthly bleeding, are extremely happy with this outpatient procedure. It is important to note that after endometrial ablation the ovaries continue to make normal amounts of hormone for the rest of your body, but without uterine lining cells, bleeding cannot occur. After surgery, women are able to return to normal activity in two or three days and look forward to life unencumbered by the fatigue and inconvenience associated with heavy bleeding.

Endometrial ablation should only be performed for women who do not wish to have any, or any more, children. Because the lining cells of the uterus are destroyed, there is no place for a developing fetus to attach within the uterus. Despite this, it is best to use some form of contraception after the procedure because there still exists the very rare possibility of pregnancy.

(For more about Hysteroscopic Myomectomy or Endometrial Ablation visit A Gynecologist’s Second Opinion: Problems with Your Period Chapter)

William H. Parker, MD

Clinical Professor, Reproductive Medicine, UC San Diego School of Medicine

Page last updated: January, 2018